"What is Dungeons and Dragons?": Dispatches from the early UK RPG Scene

Picture the scene. You're a spotty teenager in the early 80s. You've heard of this strange new "role playing game" thing, but you have no idea where to even start. Thankfully, in 1982 help arrives with not one but two books to help you on your way. What is Dungeons and Dragons? by John Butterfield, Philip Parker and Peter Honigmann. And Dicing with Dragons by Ian Livingstone. We will be returning to the latter in the future, but for now What is Dungeons and Dragons? is our focus.

Honestly, I find that dragon kinda adorably rubbish. He doesn't so much fly through the sky as hang there. This is something of a trend in the early RPG scene, especially the British RPG scene. It seems a fine example of what Andy Bartlett refers to as the Pathetic Aesthetic.

I remember really liking the "fantasy cult" advertising as well as a kid. It felt a bit naughty, an invitation into a hidden world not available to my parents. Notably, the 1984 US edition did not use that wording, I suspect for self-evident reasons.

About the Authors

The authors are all students at Eton. (I don't want to be mean about it, but the fact that three Eton schoolboys with no previous publications to their name that I can find were able to get a publishing deal with Penguin Book tells us so much about the UK class system). At the time of publication, Parker and Butterfield are 17, Honigmann is 16. They have recently set up a D&D club at Eton, in between doing rude things with crumpets and playing rugger. (I don't really know many public school boys. Is it obvious?) Interestingly, they started playing in 1977 so at ages 12/11. That sounds to me like they first met and got into the game together. Also, 1977 is when Games Workshop first printed (rather than importing) D&D so I suspect this is the edition they started with.

Introduction

This starts by introducing us to what I assume are their RPG characters. We have Slammer Kyntire, a fighter who is adventuring to get the money to buy back the farm from the landlord that's seized it and enslaved his family. Hofta Nap, a sorceress who hates necromancers. Gripper "The Skin" Longshanks who is a halfling (not hobbit by this point) looking for revenge on his original band of thiefs who betrayed him to the law. I find it telling that Hofta is a sorceress rather than a magic user. Even this early, it seems D&D players weren't feeling the necessity of sticking to the mechanical terms with their background.

It goes on to explain that these aren't real people but D&D characters and gives us some background on the game. Notably, certainly in the UK, Arneson was still being mentioned as a co-creator, even by writers I'd assume didn't have strong contacts with the gaming industry. They also describe RPGs as a "conservation between the D.M. and the players". I find this fascinating because "RPG as conservation" is often seen as a more modern take and here we see it very early on.

They see *D&D as essentially "medieval plus magic" and describe it as swords and sorcery, so it seems the term was well accepted by this point.

The thing that sticks out is their suggestion that this book would be a good companion for people who already own Basic D&D and need help "progressing" to either Expert or Advanced. This fits with my own recollection of the time (or a few years later; I'm slightly younger than the author). Very few self respecting D&D players would admit to playing Basic. It's reevaluation as a good game in its own right is very much a modern OSR thing, rather than what it was actually like back then.

1. Getting Started

The part that absolutely stands out for me here is their description of the DM's role. They reject not only the adversarial style of play, but also the "DM as neutral arbiter" popular in many OSR circles.

It should be noted that the game is not a contest between D.M. and players - he is not simply trying to kill them off. Unlike referees in football or an umpire in cricket the D.M. takes an active role in the game, not simply that of a neutral observer seeing that the players do not break the rules.

I'd argue this is an early example of "the D.M. is also a player" in the wild. A lot of the advice in this chapter is about things like how to find players (find an established club or set up your own group), make sure you have a table etc. It largely stands up with the only parts dating it being the obvious lack of any mention of the Internet and the extensive explanation of dice types.

The other things worth attention are the fact it takes the idea the players will want to map as pretty much a foregone conclusion and its comments on group size. The idea of the massive groups of Lake Geneva is out of favour here. They suggest the optimum number of PCs is five and advise splitting if you reach eight or more.

2. Character Generation

I will stick to the more unusual parts in this overview of Basic D&D on the assumption that (unlike the original) most people reading this don't need it explaining what the six stats are etc.

They give multiple generation methods. They do recommend 3d6 down the line for new players, but entirely on grounds of simplicity. Other methods they mention are 4d6 drop the lowest, rolling 12 sets of stats and choosing one set (which feels rather inelegant), rolling 3d6 six times and taking the best for each stat (which they warn us produces "super characters" which can be boring to play), roll 12 times and take the best six (less super characters not many low scores) and a paring system where you roll 6d6 for pairs of stats and split the result between the two. The last is the closest they get to point buy. Despite point buy being in other games by this point (and as we'll see later they do know a wide range of RPGs) it doesn't seem to have occurred to them that it might work in D&D. What we are seeing however is that by 1982 at least, even Basic players were experimenting with methods other than 3d6 down the line. While I'm sure some players did still use that, the idea it was most players feels like it may be a modern conceit rather then reflecting how people were playing in the old days.

As an amusing aside they rather sniffly point out that anyone who has real life experience of carrying a ten foot pole will know that they're unwieldy and suggest getting a six foot pole instead. I really wish they'd told us about their real life experience of pole carrying here.

3. Dungeon Creation

This is solid, with a step by step description of how to create a dungeon, a sample short dungeon complete with key and even a brief part about creating towns or wilderness adventures. There's not going to be much new here for experienced players, but if you want to make an old school dungeon it largely stands up today.

4. The Adventure

Again, some pretty solid advice on running old school D&D. They are very clear on what the objectives of D&D are. "Collecting treasure, gaining experience and, most importantly, staying alive". This is of course entirely correct and bluntly shows way more understanding of what D&D actually is than much of the modern D&D community. ("You can use D&D to do a high politics court intrigue campaign as long as you ignore the rules that aren't there and add your own").

They go into party roles in detail. Notably, the caller (someone who speaks for the party) is mentioned. This one does seem to be a genuinely old school approach that has largely fallen out of fashion. They say it should probably be the PC with the highest charisma but are realistic enough to acknowledge it will likely be the most talkative player. They also suggest a mapper is necessary but you should draw lots if there isn't a volunteer because "this can be pretty boring at times". My view would be that if a role is such a chore that you need to make someone do it, it's best to work out how to remove it entirely. They mention marching orders (genuinely important in old school dungeon crawls I think) and light sources. They seem to use the morale and reaction tables as written and highlight that sometimes you should try and negotiate with monsters. All in all, very old D&D specific, but they know what they're talking about.

Perhaps my favourite part of this chapter is the example of play, where they alternate between a page of narrative adventure description and a page explaining how it was done mechanically. Especially as it goes into detail, covering people playing their alignment (playing low INT characters as stupid is the approach here) and even mistakes the DM has made. I really like this approach and more modern RPGs should use it.

5 The Dungeon Master

A more in-depth explanation of the DM's role, which contains some interesting nuggets.

The book is very much from the "DM can change anything" school of thought, although it's noticeable that the example it gives is one to the advantage of players (a wandering monster table that will annihilate the PCs). So there is at least some attention given to balance and a move away from "random red dragon on level 1". They also suggest that major rules changes should take place between games, "possibly" be discussed with the players and be playtested in a "pocket universe" first. Again, this seems a move away from antagonistic DMing, an impression borne out by the fact they say that the game is "more of a cooperative effort".

They do spend an ungodly amount of time on stopping players cheating; watching them roll, making sure you can see them all etc. I am inclined to put this down to groups made up of teenage boys. It does also suggest that players are limited in what they read of the rulebooks, so they don't know about the monsters etc. Generally, I agree with this in theory, but I'm never convinced it's practical, even back then. Any keen player is going to get their own copy of the rulebook and those players are going to want to read what they've spent cash on!

They do take a somewhat harsh attempt to equipment, suggesting that if a player hasn't listed something they don't have it. Equally, they say the same should apply in the other direction; giving the example of an exploding gem that the PCs haven't explicitly picked up. So while perhaps more rigid than most modern games, it seems at least to be something they expect to be applied fairly.

They do suggest that you need to be more lenient with new players. As an example, if gargoyles can only be hit by magic weapons you should tell the players they can't hit them before combat. This does show a certain level of maturity for a group of that age.

They are in the pro fudging camp but only rarely and with caution. (They give the example of when two TPKs have happened and a third looks likely!). They're much keener on house ruling to make the game less lethal. They suggest that rather than death on 0 HP, players should be given six rounds of bleeding out to be healed in. They also advise strongly against "save or die" poison, preferring poisons that are disabling but non permanent.

Again, I find this a fascinating break from perceptions of what old D&D was played like. I'm sure killer DMs existed. But here we have an example of three teenage boys independently coming up with rules to make D&D more survivable, one assumes because "fantasy Vietnam" was less fun for them. There's possibly a generational divide between the first and second wave of role players here, but one far more complex than the "grognard versus munchkin" narrative would have us believe.

Finally, this is not a book that supports viking hat DMing. It doesn't go for campaign by committee either (it describes the best approach as "slightly democratic". But it makes clear that if your players aren't having fun you either "change your ideas" or let another player step up and become a player yourself. It could be being argued that I'm putting too much emphasis on a single player group when it comes to arguing that it shows that adversarial DMing was not the norm. But when that group wrote one of two books introducing a UK audience to D&D, I think it is highly likely it had an effect on general UK play culture. (Especially, as we shall see, because Dicing With Dragons takes a similar line on the issue).

6. Figures and Other Accessories

This chapter is largely of historical interest. The massive emphasis on figures (they use this term rather than miniatures) does suggest they were incredibly common back then. Which isn't entirely surprising; the modern equivalent is likely VTT tokens. Standard is lead (unlike plastic which is the case now) and 25 mm. They suggest they're particularly useful for converts from wargaming although I suspect that their view that wargaming armies are a thing of the past because of cost is likely the view of someone with the income of a teenage boy! (And they can't be expected to have predicted the success of Warhammer a mere year later). There's some useful stuff about painting etc.

They mention GM screens (which they call "Referee Shields") briefly and suggest a calculator is useful. Less the case now, but still applies in some games.

They're reasonably positive about modules because of their ease, while suggesting that they lack the "personal touch" of a homemade campaign. They are not positive about "dungeon geomorphs" (which seem to be dungeon maps without room descriptions) saying that compared to modules or homemade dungeons they have "the failings of both with few good points". Ouch! Although geomorphs never really took off, so they have a point.

The magazine overview is pretty extensive. They describe White Dwarf as "easily the best magazine on the market", with particular praise for Don Turnbull's Monstermark system (a largely forgotten attempt to measure monster deadliness) and Lewis Pulsipher's DMing advice. Lew was controversial back in the day, so it's nice to see someone liked him. They quite like Dragon especially the fantasy fiction in it. They are less keen on Battle where the letters pages are apparently full of modellers who resent wargamers and wargamers who resent fantasy/sci fi gamers. Gamers. Gamers never changes. They praise Ares highly, largely because of the quality of the contained games. They briefly cover the house magazines of various other games but without much detail.

They are rather snarky about fanzines. They quote Gygax's infamous quote about them ruining D&D. They also suggest that you have to take the rough with the smooth with an emphasis on the former, that most fanzines have at most two decent articles anyway and that this is despite them being roughly the same price as the superior professional magazines. One suspects they would have not been keen on the DIY element of the OSR.

7 Computers

We'll skim over this. As you can imagine, it's the part that has aged least graciously. They don't think that computers can replace the human imagination. (And they're right. Lets be honest, have you ever heard someone who talks about using AI in their games whose campaigns don't sound shit?). They do like the idea of being able to use computers to do bookeeping and other tedious stuff and also being able to search something like the Monster Manual quickly for the relevant entry. So they did predict searchable PDFs to an extent. They dislike text adventures (THORIN SINGS ABOUT GOLD) enough that they just give a brief overview of how they work. And we're pretty much done here.

8 Further Complexity**

This is a largely comparative analysis of Advanced and Expert D&D. A lot of it is rules overviews etc. which I won't go into. But while they like both, I'd say the chapter slightly leans towards Expert. While comprehensive, they find AD&D overwritten (because it fucking is shut up Gary for fuck's sake) saying that "sometimes important rules are swamped by a mass of detail" and also point out it's twice the price of Expert. They strongly do not recommend it for beginners, but in the end come down to essentially "Expert is more polished, Advanced has more in it" and recommend either to people looking to move on from Basic.

9 Other Worlds

The introduction to this made me laugh a lot.

Soon after D&D's introduction in 1974, it became obvious that, although the fundamental idea behind the rules, the role-playing concept, was a good one, the game mechanics themselves left much to be desired. The rules failed to cover large areas and were in some cases contradictory. Many people realised there was much potential for similar products with comprehensible and better organised rule.

God lads, just take D&D out the back of the stables and shoot it. They're right, obviously. It does sound like they'd actually mostly moved onto other and better games by the time of writing but the publisher made them write about D&D.

They cover a fair few other games out there in varying levels of detail. They really like En Garde! and go into detail on the mechanics, partly because in their view it's the only game truly not beholden to D&D. They're probably correct here; it's worth picking up a copy to see a game that's still really like nothing else on the market.

Of note is their metrics for choosing RPGs; their priorities are character creation, character progression, combat and the setting.

For character creation, they note that the vast majority of games follow the random generation method, while using different stats and/or. There are a handful of point buy systems mentioned (The Fantasy Trip) but they seem to be outliers. Traveller gets a special mention for its random approach to careers. They also like the fact that Traveller is one of the few games that leads to middle aged characters, obviously a great role-playing challenge for strapping young bucks like the writers.

I find the settings section more interesting. They fairly write off most fantasy RPGs as "quasi medieval", although they do praise Chivalry and Sorcery for its more historic nature. They especially like its approach to social structure. This obsession with class is perhaps one of the things that differentiates the British RPG scene from the US scene and its fantasy frontier approach. The games that really float their boat regarding setting however are Runequest and Empire of the Petal Throne. (Obviously, at this point they'd have had no idea of the latter's highly dubious political associations). Glorantha is "richly imaginative and widely developed" and Tek'umel is "excellently conceived" It's really noticeable this is far more enthusiastic language than they ever manage about D&D through all the previous chapters. This really does seem to be people who have mostly moved on from D&D writing a book about it because it's what sells. It's also interesting that they describe Runequest as "widely popular", again making clear this book is aimed at a British audience; as White Dwarf polls make clear, Runequest was always a bigger name in the UK then its home country.

They make an interesting point about science fiction settings that I hadn't noticed before.

With all the social systems of history to chose from, S.F. game designers always seem to plump for a loose confederation of worlds with a central government, in which players are free agents.

I think that's actually true, not just back then but mostly today (we've just added Cyberpunk to the cliches). And their subtle dig at Scifi RPGs for lack of originality seems like a direct hit.

They skim over post apocalyptic RPGs, describing their use of mutated animals as monsters as "D&D in Space again". I'm starting to think they may not be fans of D&D at all. Historical RPGs are similarly skimmed over (only Boot Hill is mentioned in this section). They suggest they have "obvious settings" so decide more detail is unnecessary

.

They go into detail on different combat systems, suggesting the main distinction is the dichotomy between realism and simplicity. With the addition of low to no combat RPGs, this is probably still the case. Magic is treated similarly, with them snarking at D&D's magic system for lack of realism. (They do try and counter the "how can you talk about realism with fantasy magic" argument with a rather unconvincing argument about how if it existed magic would be "more likely to work some ways than others".

Then onto character progression and more snark at D&D. (They suggest that one of the main advantages of advancement in D&D is that you can call yourself "less irritating level names"). They suggest that attempts to move away from an experience system (whether level or skill based) haven't worked, singling out Traveller as risking getting "aimless" as characters fail to improve. A design issue today, if we leave out the one shot focused games. They also think stat improvement in Tunnels and Trolls gets disproportionate which it absolutely does and is part of the appeal. Again En Garde! is positively highlighted as the one system to break with D&D entirely by using social status as a progression metric. Probably true; En Garde! really does have very little in common with D&D, even less than a narrative RPG like Apocalypse World (even if the fans of the latter will insist that playbooks aren't really classes and you're a big meany for suggesting that a party role and list of feats is pretty much the same thing and their thing is different so shut up).

They briefly cover some D&D adjacent boardgames. They find Sorcerer's Cave fun but shallow and only really worth it if you're trying to get your family into board games. They like Mystic Wood by the same publisher a lot more, partly because of the use of clear objectives rather than a vague points system. I've never played Castle Valkeburg and they're largely unimpressed by its "flimsy" treasure rules, "uninspired" magic mechanics and "out of place" soldiers fight orcs setting. The frontage rules are apparently quite good though. They're a big fan of Chaosium's games (Elric, King Arthur's Knights and Dragon Pass). I am now about 90% sure this book was written by Runequest partisans. Divine Right, now much loved in hindsight is less to their taste being too complex for family gamers and too simple for veteran wargamers. They only suggest playing the armies version of War of the Ring and are ambivalent about Dune. Finally, for something completely different they mention Killer. They suggest that if you take it seriously it's the closest to a "real life role playing game" and very good, but often it "tends to degenerate into a situation where a handful of psychos wipe each other out, causing a good deal of mess to bystanders and innocent bystanders. One wonders if there is a story behind that. I also wonder if they ever discovered the LRP Treasure Trap (started April 1982) as their comments about real life role play strike me as people crying out for that kind of thing.

This is probably my favourite chapter. At times a passion shines through that isn't quite there in the rest of the book. And they're free to give opinions rather than facts. And actually, I do think that a book about D&D should be written by people with a wider context of RPGs, for the same reason I don't think books about The Beatles should be written by people who've never heard another band and I wouldn't care about what someone who only eats as McDonalds thinks about food. Even moreso with RPGs, where the intellectual in-curiosity needed to have not at least tried another RPG in time goes directly against what I see as important to what RPGs are about. If any 5e only players see this as an attack on them, it absolutely is

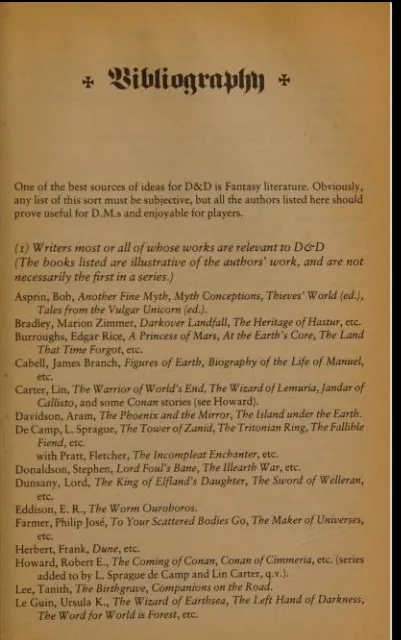

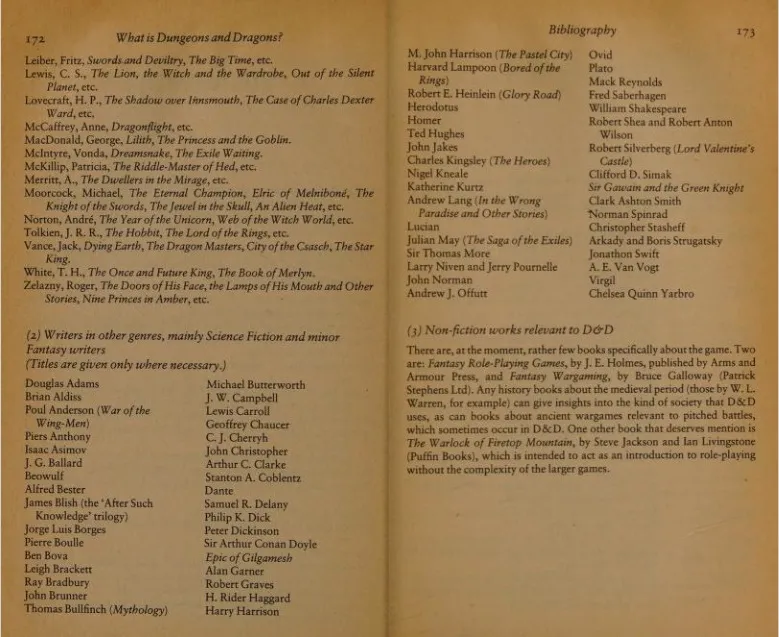

And so we near the end. There's a list of game manufacturers, a great idea at the time, entirely useless now. A glossary and I refuse to go point through point definitions of "holy water" and "copper piece". The bibliography however (a kind of Appendix N of their own) is fascinating and worth reproducing in full.

While there's obviously some crossover with Appendix N, what's interesting is how much is different. There's a lot more British authors (T.H. White, C.S Lewis). I really liked this little insight into what teenage geeks of the time might be reading. And thought it showed that while they may have searched out the books from Appendix N this was more then just them parroting it, with tastes and influences outside of that. I take the second bibliography less seriously. It is hard to think that a bibliography that lists Homer, Virgil, John Norman and Robert Anton Wilson isn't just them showing off by listing everything they've read. I did find it highly amusing that they listed Fantasy Wargaming as a non fiction book rather than a RPG. But anyone who has tried reading the included RPG will consider that entirely justified.

And finally at the end of our long and epic quest (yes, I know that's cringe, it's two in the morning fuck you) we get to the author's notes. This is really interesting because of how they express their personality through apologies. Writing an apology section is so British it hurts. We have an apology for not including prices (they fairly say these date too quickly). The second is for the fact they wrote the book as three, taking different chapters and so it may have stylistic shifts. They're right and this does make the difference between say the "other RPGs" and the much more formal "how to run a dungeon" sections make a lot of sense. However, they do want to make clear that it's a collective work and they've all read it and take responsibility for the contents. They apologise for the fact the book is aimed at different experience levels and hope both veterans and new players will find something of use. They also apologise for any accidental plagiarism of things they've read on D&D. Which is sweet, but I'm pretty sure most professional authors deal with the issue of unconscious influence by ignoring it entirely.

The bit that stands out for me however is an apology to their "female readership" for their use of the generic "he". They say they found "he/she" too clumsy and so went with the generic "he" because of most players being male. However, they accept this is not "totally satisfactory". They also recognise that including a female wizard to try and redress the balance is a "token gesture and rather stereotyped to boot" and defend themselves by suggesting "the problem lies with the English language, not us".

I'm inclined to be charitable here. We have a group of schoolboys in 1982 who recognise that exclusionary language is something of an issue. They don't have a solution, but they recognise their token solutions don't quite cut it. It's hard not to contrast this with game designers twice their age claiming women and girls don't like RPGs because they have female brains and biology makes them not want to play D&D.

And finally finally, there's some really interesting names in the acknowledgements for help with the book. Having checked that the timing checks out, I'm pretty sure "Mr Hammond" is head of classics and housemaster of Eton, who gained some fame for comments in made in Boris Johnson's report in 1982. Andy Slack is almost certainly the game designer of the same name. Captain Flint intrigues me, as one assumes they weren't actually helped by a fictional pirate. The other point of interest is one that runs counter to the stereotype of the early RPG scene having no women or girls. I'm not going to claim it was 50/50, but one "Colette - a different one" is mentioned in the acknowledgements as a fellow player. Sadly, the mysterious Colette and why she's a different Colette is never explained!

Overall, this was a fascinating glimpse into a British RPG scene that once was. Both because of what's changed and what hasn't. The authors are generally likeable and at least reasonable at prose. The book can be a bit rough in places (and I will admit to skimming detailed descriptions of D&D mechanics but overall there's something rather charming about it.

Largely of interest to nostalgists and those with an interest in RPG history, but a valuable artifact to those wanting to look at how things were on these shores.

6/10